London-based food designer Francesca Sarti cooks up a new project for Disegno and Gaggenau

Time to Eat

The topics of food and time occupy ever-greater spaces in the cultural landscape these days. The pace of life, by popular consensus, seems to be accelerating—the most widely proclaimed complaint across the Western world being, “I’m just too busy.” Meanwhile, in response to this unrelenting drive toward efficiency (and its adverse impact on quality of life), a number of food-related movements—organic, slow, farm-to-table, and so on—have risen up alongside an increasing interest in mindfulness and ethical living. So many of us are looking for ways to get back to the all-important basics.

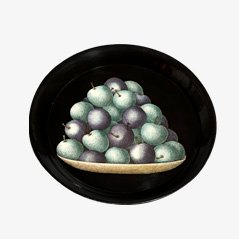

Our friends at Disegno magazine, in partnership with kitchenwares brand Gaggenau and food design studio Arabeschi di Latte, recently took up these on-the-pulse themes to beautiful effect. The aptly titled Food and Time project includes a series of recipes and imagery meant to inspire us to slow down and think about what nourishes us, body and soul.

We sat down with Francesca Sarti, Arabeschi di Latte’s founder and a long-time, pioneering food designer, to learn more about how design thinking can be harnessed in service of conscious eating. Over the last 15 years, Sarti has been steadily commissioned to create performative, interactive events and installations for the likes of the Triennale Design Museum, Tom Dixon, Veuve Clicquot, Selfridges, Zegna, Molteni, New York Times Style Magazine, Bitossi, and more. Read on for some delicious insights into her work—and a few tasty recipes to boot.

WC: The interdisciplinary field of food design has become one of the fastest growing areas of contemporary design practice in the past decade. For those who may be new to the subject, can you give a brief background on where it came from and why it’s such a compelling area of investigation today?

FS: The meaning of the expression “food design” has changed a lot in the last 10 years. When I founded Arabeschi di Latte in 2001, the term was associated with the food industry and the design of industrial food products, while I have always seen it more associated with experience, interaction, and relationships. With Arabeschi di Latte I have tried to reshape this binomial, creating interactive experiences and using food as a tool to investigate and communicate social trends and conditions, customs, and rituals around the world—to make statements, but not necessarily products.

Today there are more and more designers, artists, and architects exploring the food theme, and “food design” is evolving fast. I think that the reason for this success is to be found in the dual nature of food: it is something truly necessary and something that speaks of culture, traditions, and pleasure.

WC: How does food—or our relationship with food—improve through food design?

FS: Food is such a powerful tool for communication. It’s perfect for storytelling and expressing ideas in an immediate and effective way. Therefore, I think food design can help create awareness of many topics, making important statements that invite people to take action to improve the quality of food and the quality of life. I like to imagine food design as a form of activism.

WC: How does your work relate to the slow food movement?

FS: I share most of the slow food principles, and I think the movement should collaborate more with designers in the future to view important issues from a different and unexpected perspective that could bring interesting solutions.

WC: How does your work relate to more traditional design practices, e.g. product design?

FS: I think the creative process is very similar to other branches of design; it’s just that food has its own peculiarities. First of all, food is, as already mentioned, something that’s necessary, primary, with a lot of cultural and even sensual implications. And its perishable nature forces you to always take in consideration an important factor: time.

WC: Can you tell us more about your recent project with Disegno and Gaggenau?

FS: Because I see food’s subtle, suggestive relation with sliding time as one of its most essential characteristics, I thought it was a good subject to explore for the Disegno/Gaggenau commission.

Time often reshapes, transforms, affects, or alters food’s appearance and structure, without necessarily changing its own core nature. Ripening takes days; boiling or toasting takes minutes; while roasting can take hours and fermenting might take months. Moments, hours, days, weeks, years—or even just few seconds—can singularly define food.

WC: What are you working on next?

FS: After the collaboration in Milan with The Restaurant designed by Tom Dixon, I will keep working on the "four elements" theme for Caesarstone, along with a lot of consultancies, special events, and workshops. I’m also developing a new project around water, building on the Ocean Water Bar I created for Selfridges last summer. I will also continue my beloved research around food, women, and empowerment. I’m collecting a lot of interesting stories that I hope I will be able to share in some form soon, in due time.

Thanks so much, Francesca! Here are a few of her recipes from Food and Time:

Fermenting—Apple Wine

This recipe is a variation on mead, one of the oldest fermented drinks on earth. The sugar reacts with yeast to become, over time, alcohol. During this process, bubbles rise to the surface.

Ingredients

7 l water

500 g soft brown sugar

500 g white sugar

4 apples, cut into wedges

1 lemon, cut into cubes with the peel

1/2 tsp dried yeast

A handful of raisins

Bring the water and both sugars to a boil. As soon as the sugars have melted, remove from heat. Add the cubed lemon and apple wedges. Let the mixture cool to room temperature and then add the yeast. Add the liquid together with the lemons, apples, and a handful of raisins to a wide necked glass bottle. Put the bottle in a cool place and drink when the raisins rise to the surface—after about three days.

Maturing—Aromatic Labneh

Originally hailing from the Middle East, labneh is a smooth, soft cheese that can be easily made at home by placing Greek yoghurt in a cloth to mature. During the maturation process, water seeps through the fabric and becomes a means to measure time: each drip is like a second. The cheese is ready to eat when the drips become more infrequent and eventually cease.

Ingredients

1 kg Greek yoghurt

1 tsp sea salt

1 vanilla pod, scraped

Olive oil

Fresh basil leaves, finely shredded

1 unwaxed lemon, zested

Line a sieve with a double layer of muslin and place it over a bowl. Mix the yoghurt with the salt and the vanilla seeds. Put the yoghurt onto the fabric and tie the fabric up like a bag. Suspend this bag with kitchen string from one rack in the fridge, placing it over a bowl. Let the yoghurt drip for 24 to 48 hours, giving the bag a squeeze a couple of times a day. Unwrap the labneh, break it into chunks and roll into balls with wet hands. Roll the balls in the shredded basil leaves and the grated lemon peel. Take a sterilized jar (1.5l), pour some olive oil into the jar and start putting the balls in. Add more oil as you go, so the cheese balls don't stick together. Cover the balls completely with oil. Refrigerate and leave for two days. The cheese balls last for two weeks in the refrigerator.

For more of Arabeschi di Latte’s recipes, head over to Disegno.

-

Text by

-

Wava Carpenter

After studying Design History, Wava has worn many hats in support of design culture: teaching design studies, curating exhibitions, overseeing commissions, organizing talks, writing articles—all of which informs her work now as Pamono’s Editor-in-Chief.

-